language-history

Archived insight from languages before talking about natural languages

The Evolution and Dynamics of Language

Introduction

Language evolution and change reveal critical insights into human history, cognition, and social dynamics. From ancient communication to modern technological shifts, languages adapt continually. As a data scientist, I aim to harness data and analytical methods to explore these dynamics. By applying advanced analytics to linguistic data, I seek to identify patterns that illustrate the complexities of human communication.

Understanding these processes enriches our appreciation of linguistic diversity and sheds light on broader cultural and societal trends. The future will see language preservation efforts intersecting with globalization, while advancements in digital communication and AI could redefine language change. Additionally, factors like climate change and migration may influence language distribution.

By analyzing language evolution through a data-driven lens, we can better navigate and influence the future of human communication. Our languages will remain a testament to the rich tapestry of human experience and adaptation.

History

The origins of language can be traced back to early human ancestors who developed basic forms of communication. Historical linguistics studies the evolution of languages over time, examining changes in phonetics, syntax, and semantics. For instance, the Great Vowel Shift in English, which occurred between the 15th and 18th centuries, significantly altered the pronunciation of vowels. Research papers such as “The Evolution of Language” by Fitch (2010) provide insights into the biological and cultural factors that have shaped language development over millennia.

Early forms of human communication likely involved a combination of gestures, vocalizations, and facial expressions. As our ancestors’ cognitive abilities evolved, so did their capacity for more complex communication. The development of symbolic thought and the ability to create and use tools may have played crucial roles in the emergence of language as we know it today.

Typology

Linguistic typology is the study of the structural features of languages and their classification into different types. It includes phonological typology, which examines sound systems; syntactic typology, which looks at sentence structure; and lexical typology, which focuses on vocabulary. For example, languages can be classified as analytic or synthetic based on their use of inflectional morphology. The World Atlas of Language Structures (WALS) is a valuable resource for understanding linguistic diversity and typological patterns.

Some key typological classifications include:

- Word order typology (e.g., SVO, SOV, VSO)

- Morphological typology (e.g., isolating, agglutinative, fusional)

- Phonological typology (e.g., tonal vs. non-tonal languages)

- Alignment typology (e.g., nominative-accusative, ergative-absolutive)

Understanding these classifications helps linguists compare and analyze languages across different families and regions.

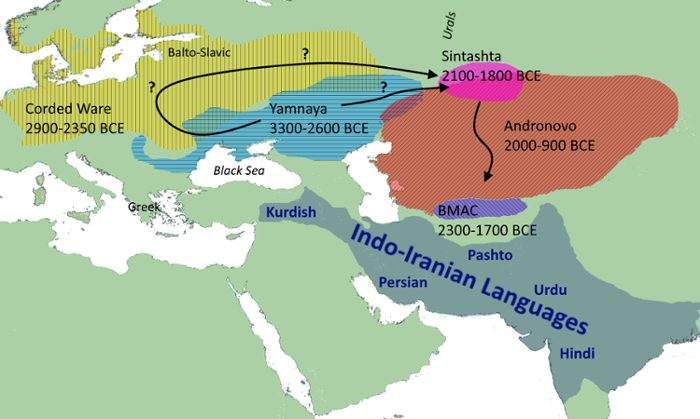

Indo-European Languages

The Indo-European language family is one of the largest and most widely spoken in the world. It includes many of the languages of Europe, as well as several major languages in South Asia and Southwest Asia. Here are more details on the key branches of the Indo-European family:

The Indo-European language family is one of the largest and most widely spoken in the world. Here’s a detailed look at the key branches, their features, and sub-branches:

Germanic Language

Definition: A branch of the Indo-European language family that includes languages spoken primarily in Northern and Western Europe.

Features:

- Grimm’s Law and Verner’s Law (systematic sound changes)

- Weak and strong verb conjugations

- Use of modal verbs

- Stress-timed rhythm in many languages

- Vowel alternation (ablaut) in strong verbs and some nouns

- Tendency towards analytic structures

Branches:

- North Germanic (Scandinavian): Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, Icelandic, Faroese

- West Germanic: English, German, Dutch, Frisian, Yiddish, Low German

- East Germanic: Gothic (extinct)

Romance Language

Definition: A branch of the Indo-European language family derived from Latin, spoken mainly in Southern and Western Europe.

Features:

- Development of definite and indefinite articles

- Formation of future and conditional tenses from infinitive + habere

- Retention of grammatical gender

- Development and later loss of a two-case system in some languages

- Emergence of the subjunctive mood

- Widespread use of reflexive verbs

Branches:

- Italo-Western: Italian, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, Occitan, Romansh

- Eastern Romance: Romanian, Aromanian

- Sardinian (sometimes considered a separate branch)

Slavic Language

Definition: A branch of the Indo-European language family spoken primarily in Eastern Europe and parts of Central and Northern Asia.

Features:

- Aspect pairs in verbs (perfective/imperfective)

- Palatalization of consonants as a grammatical feature

- Free word order due to extensive case systems

- Distinction between animate and inanimate nouns in some case forms

- Productive word formation through prefixes and suffixes

Branches:

- East Slavic: Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian

- West Slavic: Polish, Czech, Slovak, Sorbian

- South Slavic: Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian, Slovene, Bulgarian, Macedonian

Indo-Aryan Language

Definition: A branch of the Indo-European language family encompassing languages spoken in the Indian subcontinent and Iran.

Features:

- Sanskrit’s elaborate system of compound words

- Retroflex consonants in many Indo-Aryan languages

- Ergativity in some languages

- Use of different writing systems (Perso-Arabic, Devanagari)

- Extensive use of postpositions

- SOV (Subject-Object-Verb) word order in many languages

Branches:

- Indo-Aryan: Hindi, Urdu, Bengali, Punjabi, Marathi, Gujarati, Nepali

- Iranian: Persian (Farsi), Pashto, Kurdish, Ossetic, Tajik

- Nuristani (sometimes considered a third branch)

Celtic Language

Definition: A branch of the Indo-European language family primarily spoken in the British Isles and Brittany.

Features:

- Initial consonant mutations

- VSO (Verb-Subject-Object) word order

- Use of periphrastic constructions for verb tenses

- Inflected prepositions

- Distinction between inclusive and exclusive first-person plural pronouns in some languages

- Use of a verbal noun system instead of infinitives

Branches:

- Goidelic: Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Manx

- Brythonic: Welsh, Breton, Cornish

- Continental Celtic: Gaulish, Celtiberian (all extinct)

Hellenic Language

Definition: A branch of the Indo-European language family that includes the Greek language, with a long literary and historical tradition.

Features:

- Retention of three grammatical voices: active, middle, and passive

- Complex system of participles

- Retention of a productive aorist tense

- Use of the optative mood (now largely obsolete in Modern Greek)

- Polytonic orthography in Ancient Greek

- Extensive use of compounding in word formation

Branches:

- Attic-Ionic: Ancient Attic, Ionic, Koine Greek

- Modern Greek: Standard Modern Greek and its dialects

- Ancient dialects: Doric, Aeolic, Arcadocypriot (all extinct)

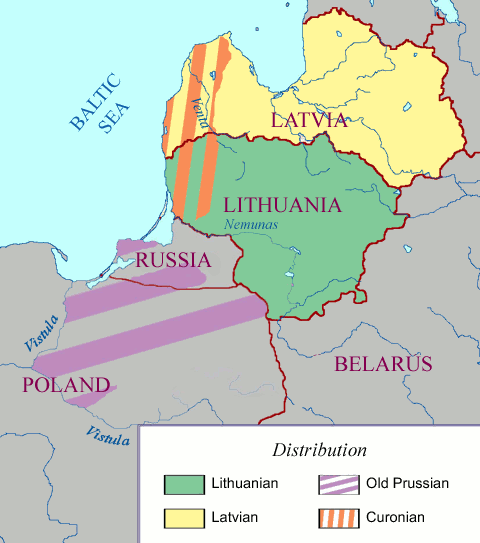

Baltic Language

Definition: A branch of the Indo-European language family, primarily spoken in the Baltic region of Europe.

Features:

- Retention of the dual number in Old Prussian (extinct)

- Complex tonal systems, especially in Lithuanian

- Highly conservative nature, retaining many Proto-Indo-European features

- Seven cases in Lithuanian

- Distinction between definite and indefinite adjectives

- Retention of the neuter gender in Latvian pronouns and adjectives

Branches:

- East Baltic: Lithuanian, Latvian

- West Baltic: Old Prussian (extinct)

The study of Indo-European languages has been crucial in developing methods of historical linguistics and understanding language evolution. Comparative methods have allowed linguists to reconstruct the hypothetical Proto-Indo-European language, providing insights into the prehistoric spread and diversification of these languages.

Afro-Asiatic Languages

The Afro-Asiatic language family is a major group primarily spoken in North Africa, the Horn of Africa, and Southwest Asia. It has played a significant role in the development of writing systems, with Egyptian hieroglyphs and the Phoenician alphabet (which gave rise to many modern alphabets) originating from this family. Here’s a detailed look at the key branches, their features, and sub-branches:

Semitic Language

Definition: A branch of the Afroasiatic language family, primarily spoken in the Middle East and parts of North Africa.

Features:

- Triconsonantal roots (most words derived from three-consonant roots)

- Nonconcatenative morphology (word formation by changing internal vowel patterns)

- Presence of pharyngeal and emphatic consonants

- Grammatical gender (masculine and feminine)

- VSO (Verb-Subject-Object) word order in many languages

- Use of broken plurals (changing the internal structure of a word to form plurals)

Branches:

- East Semitic: Akkadian (extinct)

- West Semitic:

- Northwest Semitic: Hebrew, Aramaic, Phoenician

- Arabic

- Ethiopian Semitic: Amharic, Tigrinya, Ge’ez (liturgical)

Egyptian Language

Definition: An ancient language of Egypt, known for its hieroglyphic writing system and significant historical influence.

Features:

- Hieroglyphic writing system (one of the world’s earliest writing systems)

- VSO word order

- Distinction between stative and dynamic verbs

- Use of determinatives in writing (signs indicating semantic category)

- Complex system of honorifics and formal language

Branches:

- Old Egyptian

- Middle Egyptian

- Late Egyptian

- Demotic

- Coptic (the only surviving stage, now a liturgical language)

Berber Language

Definition: A group of closely related languages spoken by the Berber people in North Africa.

Features:

- Initial-vowel ablaut (changing the first vowel of a word for grammatical purposes)

- Extensive use of consonant clusters

- Presence of emphatic consonants

- VSO word order

- Two grammatical genders (masculine and feminine)

- Use of a construct state (a grammatical structure linking two nouns)

Branches:

- Northern Berber: Tashelhiyt, Tarifit, Kabyle

- Tuareg

- Zenaga

- Eastern Berber: Siwa, Awjila-Sokna

Cushitic Language

Definition: A branch of the Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Horn of Africa.

Features:

- Extensive case systems in some languages

- Tonal distinctions in many languages

- SOV (Subject-Object-Verb) word order

- Convergence of grammatical gender with biological sex

- Use of suffix-conjugated verbs

- Presence of ejective consonants in some languages

Branches:

- North Cushitic: Beja

- Central Cushitic: Agaw languages

- East Cushitic: Somali, Oromo, Afar

- South Cushitic: Iraqw, Burunge

Chadic Language

Definition: A branch of the Afroasiatic language family, primarily spoken in Chad and surrounding areas.

Features:

- Tonal systems used for both lexical and grammatical distinctions

- Presence of glottalized consonants

- Gender distinction in pronouns and sometimes in nouns

- Use of verbal extensions to modify verb meanings

- SVO (Subject-Verb-Object) word order in many languages

Branches:

- West Chadic: Hausa, Angas, Bole

- Central Chadic: Bura, Marghi

- East Chadic: Kera, Lele

- Masa languages (sometimes considered a separate branch)

Omotic Language

Definition: A branch of the Afroasiatic language family primarily spoken in southwestern Ethiopia.

Features:

- SOV word order

- Complex tone systems

- Use of converbs (non-finite verb forms)

- Extensive case marking

- Presence of ejective consonants

- Gender systems in some languages

Branches:

- North Omotic: Dizi, Sheko

- South Omotic: Aari, Hamer-Banna

- Mao (sometimes considered a separate branch)

The Afro-Asiatic language family has had a profound impact on the linguistic landscape of North Africa and the Middle East. The spread of Arabic through Islamic expansion has been particularly significant, influencing vocabulary and sometimes grammar in many non-Arabic languages of the region. The family’s contributions to writing systems, including the development of the alphabet, have had global implications for literacy and communication.

Sino-Tibetan Languages

The Sino-Tibetan language family is one of the largest language families in the world, encompassing languages spoken in East Asia, Southeast Asia, and parts of South Asia. Here’s a detailed look at its key branches, features, and sub-branches:

Sinitic Languages

Definition: A branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family that includes the Chinese languages.

Features:

- Tonal languages with multiple tones

- Monosyllabic morphemes

- Lack of inflectional morphology

- Use of classifiers

- Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) word order

Branches:

- Mandarin: Standard Chinese, Sichuanese, Northeastern Mandarin

- Yue: Cantonese, Taishanese

- Wu: Shanghainese, Suzhounese

- Min: Hokkien, Teochew

- Xiang: Hunanese

- Hakka: Hakka Chinese

- Gan: Jiangxi Chinese

Tibeto-Burman Languages

Definition: A branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family spoken in the Himalayan region, Southeast Asia, and parts of South Asia.

Features:

- Tonal and non-tonal languages

- Agglutinative and isolating morphology

- Verb-final (SOV) word order

- Use of postpositions

- Complex verb morphology in some languages

Branches:

- Tibetan: Central Tibetan, Amdo Tibetan, Khams Tibetan

- Burmese: Standard Burmese, Arakanese

- Karenic: Sgaw Karen, Pwo Karen

- Bodo-Garo: Bodo, Garo

- Kuki-Chin: Mizo, Hmar

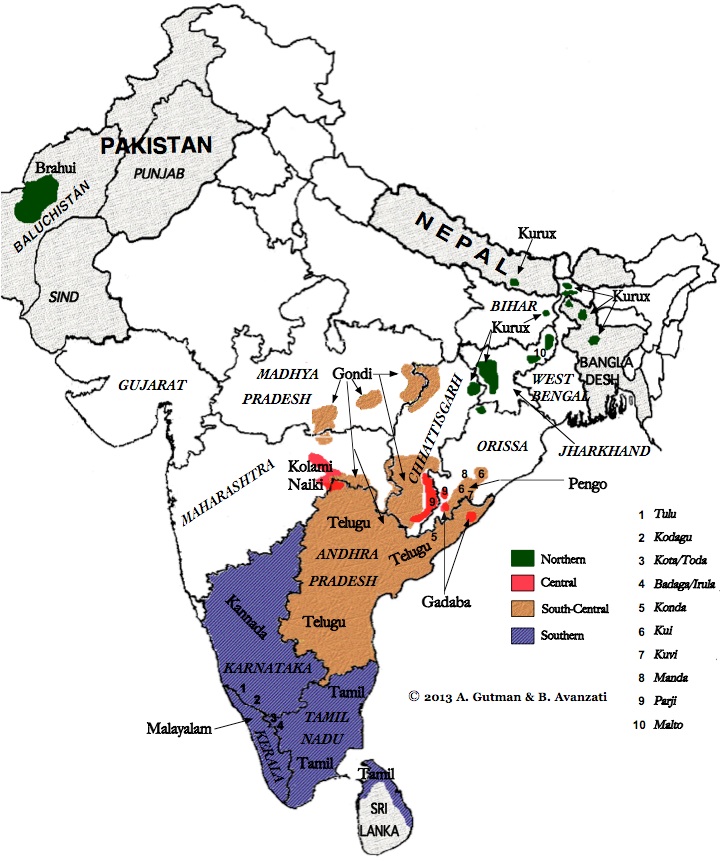

Dravidian Languages

The Dravidian language family is primarily spoken in South India and parts of Central and Eastern India. Here’s a detailed look at its key branches, features, and sub-branches:

Definition: A language family spoken mainly in southern India and parts of eastern and central India.

Features:

- Agglutinative morphology

- Retroflex consonants

- SOV (Subject-Object-Verb) word order

- Use of postpositions

- Extensive use of compound verbs

Branches:

- South Dravidian: Tamil, Kannada, Malayalam, Tulu

- Central Dravidian: Telugu, Gondi, Konda

- North Dravidian: Brahui, Kurukh, Malto

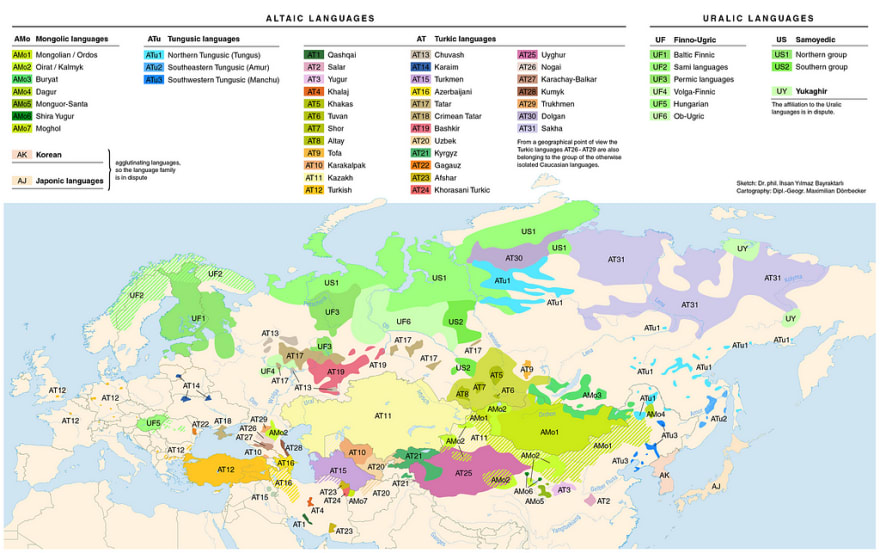

Altaic Languages

The Altaic language family is a controversial grouping that includes languages spoken in Central Asia, Siberia, and parts of East Asia. Here’s a detailed look at its key branches, features, and sub-branches:

Definition: A proposed language family that includes Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic languages.

Features:

- Agglutinative morphology

- Vowel harmony

- SOV (Subject-Object-Verb) word order

- Use of postpositions

- Lack of grammatical gender

Branches:

- Turkic: Turkish, Uzbek, Kazakh, Uighur

- Mongolic: Mongolian, Buryat, Kalmyk

- Tungusic: Manchu, Evenki, Nanai

Austroasiatic Languages

The Austroasiatic language family is spoken in Southeast Asia and parts of India. Here’s a detailed look at its key branches, features, and sub-branches:

Definition: A language family spoken in Southeast Asia and parts of India.

Features:

- Monosyllabic and disyllabic morphemes

- Tonal and non-tonal languages

- SVO (Subject-Verb-Object) word order

- Use of classifiers

- Extensive use of infixes

Branches:

- Mon-Khmer: Vietnamese, Khmer, Mon

- Munda: Santali, Mundari, Ho

Why Languages Change

Languages change due to a variety of social, cultural, and technological factors. Social factors include language contact, where speakers of different languages interact and influence each other. Cultural factors involve shifts in societal norms and values, while technological advancements can introduce new vocabulary and expressions. For example, the rise of the internet has led to the creation of new words and phrases. Research papers such as “Language Change: Progress or Decay?” by Jean Aitchison explore the mechanisms and motivations behind language change.

Other factors contributing to language change include:

- Generational differences in language use

- Economic and political influences

- Media and popular culture

- Education and literacy rates

- Globalization and international communication

When Languages Change

Language change can be triggered by events such as migration, conquest, or technological innovation. For instance, the Norman Conquest of England in 1066 brought significant French influence to the English language, leading to changes in vocabulary and grammar. Similarly, the spread of the printing press in the 15th century standardized spelling and grammar in many European languages. Studies like “The Dynamics of Language Evolution” by Salikoko S. Mufwene examine the conditions under which languages change and the processes involved.

Language change can occur gradually over centuries or more rapidly in response to sudden societal shifts. Some examples of rapid language change include:

- The impact of social media on communication styles

- The adoption of loanwords following cultural exchange

- Language revival efforts for endangered languages

- The emergence of pidgins and creoles in contact situations

How Grammar Changes

Grammatical structures evolve over time through processes such as grammaticalization, where words or phrases gradually become grammatical markers. For example, the English future tense marker “will” originated from the Old English verb “willan,” meaning “to want.” Changes in syntax, such as the shift from Old English’s flexible word order to Modern English’s more rigid subject-verb-object order, also illustrate grammatical evolution. Research on grammatical change, such as “Grammaticalization” by Paul J. Hopper and Elizabeth Closs Traugott, provides detailed analyses of these processes.

Other types of grammatical changes include:

- Phonological changes affecting morphology

- Simplification or complexification of inflectional systems

- Changes in word order preferences

- Development or loss of grammatical categories (e.g., case systems, aspectual distinctions)

Environmental Impact on Language Changes

Environmental factors, including geography, climate, and contact with other cultures, play a significant role in language change. Geographic isolation can lead to the development of distinct dialects, while contact with other cultures can result in language convergence or the borrowing of words and structures. For example, the influence of Arabic on Spanish during the Moorish occupation of the Iberian Peninsula is evident in many Spanish words of Arabic origin. Case studies in works like “Language Contact and Change” by Ernst Håkon Jahr illustrate the impact of environmental factors on language evolution.

Some environmental factors affecting language include:

- Topography (e.g., mountains, rivers creating natural barriers)

- Climate (influencing vocabulary related to local flora, fauna, and weather)

- Population density and urbanization

- Trade routes and economic patterns

- Political boundaries and language policies

Art in Language

Art and language are deeply intertwined, with literature, poetry, and other forms of artistic expression reflecting and shaping linguistic trends. The use of metaphor, symbolism, and other literary devices enriches language and provides insights into cultural and historical contexts. For example, the works of Shakespeare have had a profound impact on the English language, introducing new words and expressions. Research on the relationship between art and language, such as “The Art of Language Invention” by David J. Peterson, explores how artistic creativity influences linguistic development.

Artistic influences on language include:

- Poetic devices shaping phonological patterns

- Literary movements affecting writing styles and vocabulary

- Visual art inspiring new ways of describing color and form

- Music and oral traditions preserving archaic language forms

- Film and theater introducing new dialects and expressions

Language Contact and Borrowing

Language contact occurs when speakers of different languages interact, leading to borrowing and influence among languages. This can happen through trade, migration, colonization, or cultural exchange. The effects of language contact can lead to the emergence of pidgins and creoles, as well as the adoption of vocabulary, grammar, and phonetic features.

1. Pidgins:

- Simplified languages that develop as a means of communication between speakers of different native languages.

- Characterized by a limited vocabulary and simplified grammar.

- Often arise in contexts such as trade, where no common language exists.

2. Creoles:

- Fully developed languages that evolve from pidgins when children grow up learning the pidgin as their first language.

- Creoles typically have more complex grammar and vocabulary than pidgins.

- Examples include Haitian Creole (derived from French) and Tok Pisin (derived from English).

3. Borrowing:

- The incorporation of words and expressions from one language into another.

- This can occur at various levels, including phonetic (sound changes), morphological (word forms), and syntactic (sentence structure).

- Examples include the borrowing of “coffee” from Arabic into many languages or “café” from French into English.

Language contact plays a significant role in the evolution of languages, contributing to linguistic diversity and change.

What is Natural Language?

Natural language refers to the languages spoken, written, or signed by humans for general communication. It is distinguished from artificial or constructed languages, such as programming languages or international auxiliary languages like Esperanto. Natural languages evolve organically within communities and are characterized by their complexity, ambiguity, and ability to express a wide range of human experiences and emotions.

Key features of natural languages include:

- Phonological systems (sound patterns)

- Morphological structures (word formation)

- Syntactic rules (sentence structure)

- Semantic content (meaning)

- Pragmatic use (context-dependent interpretation)

The study of natural language processing (NLP) in computer science aims to enable machines to understand and generate human language, bridging the gap between human communication and artificial intelligence.

Conclusion

The study of language evolution and change provides fascinating insights into human history, cognition, and social dynamics. From the ancient origins of communication to the rapid changes brought about by modern technology, languages continue to adapt and evolve. Understanding these processes not only enhances our appreciation of linguistic diversity but also offers valuable perspectives on human culture and society.

As we look to the future, the interplay between language preservation efforts and the forces of globalization will likely shape the linguistic landscape. The ongoing development of digital communication tools and artificial intelligence may introduce new dimensions to language change, while climate change and population movements could alter the geographic distribution of languages.

By studying the past and present of language evolution, we can better prepare for and shape the future of human communication. Whether through art, technology, or everyday interactions, our languages will continue to reflect the rich tapestry of human experience and adaptation.